The Home Children, an important piece of Canadian history

This site is dedicated to raising awareness of the British Home Child Movement and to recognizing the contributions these little immigrants made to Canada. Their stories inspire others who face loneliness and exile from their people.

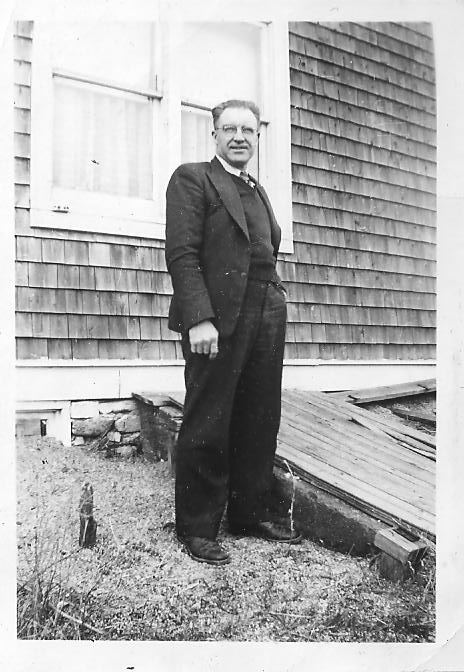

Ernest Dixon 1891-1986

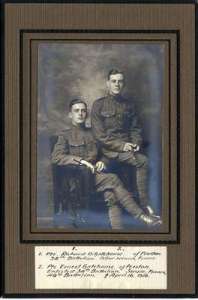

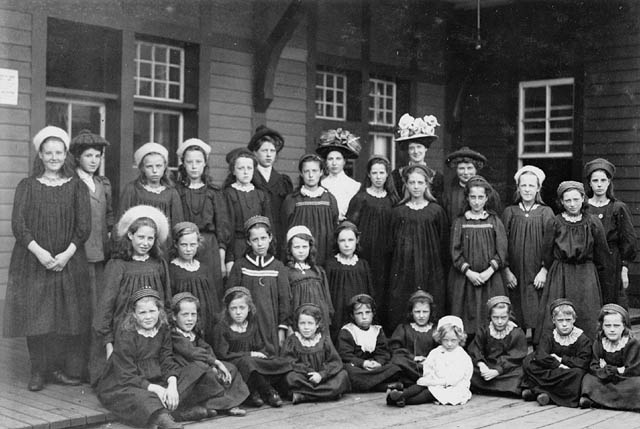

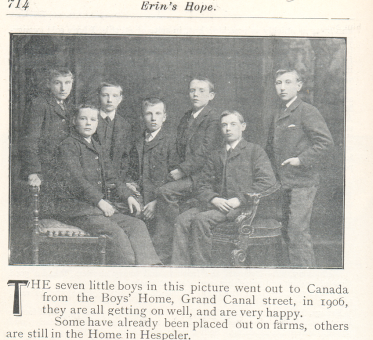

Sharon Moore of Ireland dropped in to Promises of Home to say that one of the boys in this photo that appeared with William Edwin Hunt’s story is her great grand uncle, Ernest Dixon. Ernest is believed to be the one second from right. Sharon’s family recently discovered that Ernest was a British Home Child. Sharon has found relatives in Canada, descendants of Ernest’s sister, Ellen.

Sharon writes, “I truly believe that history and ancestors have a way of taking us places in order to find them, My sister emigrated to Canada in 1988 and lives in the Halton Hills, not too far from where Ernest was sent and lived as a young man.”

Thanks to Sharon for sharing the information used to write his story.

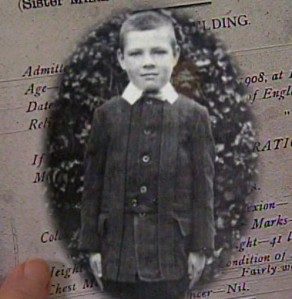

Like many child immigrants, the event that led to Ernest’s coming to Canada was the death of a parent. He was born on May 25, 1891, into a hardworking, successful Irish family, the youngest of six children. When Ernest was ten, his mother died. By this time, all the Dixon children, except for Ernest and one sister had grown up and left home.

Ernest’s father struggled after the death of his wife and ended up living at a home for destitute men.

Ernest was sent to Smyly’s Homes for Children.

Fifteen year-old Ernest Dixon arrived in Canada on May 3, 1906 on the S.S. Tunisian. He was employed as an apprentice by Clarke & Demill, a manufacturer of woodworking machinery in Hespeler. They reported that Ernest was “a quiet, good lad doing well and learning his trade as a lathe turner.”

After he reached the legal age of eighteen, he officially left the care of Smyly’s. Ernest continued to work for Clarke & Demill. He boarded with his employer but spent most evenings at the place he considered his Canadian home, The Coombe, owned by Smyly’s and a home to many Irish boys who came to Canada. There, he played and socialized with other boys from his homeland.

At age twenty, Ernest enrolled in a drafting course at Galt Business College where he joined the football and lacrosse teams. An inspector from Smyly’s described him as “quiet and steady, careful of his earnings” and noted that he was thinking of buying his own home.”

Smyly’s continued to monitor Ernest’s progress long after his eighteenth birthday. In 1916, he married Ethel Hodgeson and settled in Hespeler where he lived until 1924 when he moved to Detroit to work as a machinist in an auto plant.

Ernest’s niece, Bertha, immigrated to Canada in the 1940s and visited him in Michigan often. He was fondly known to her and her children as Uncle Ernie. Ernest and Ethel had no children. He died on June 15, 1986 in Grosse Point Farms, Michigan.

***

Note: Smyly’s introduced children to Canadian life more gently than most other organizations. Some stayed at the transition home in Hespeler, The Coombe, for months to allow them to integrate into the community gradually. Smyly’s usually placed child immigrants in homes and farms within easy monitoring distance.

***

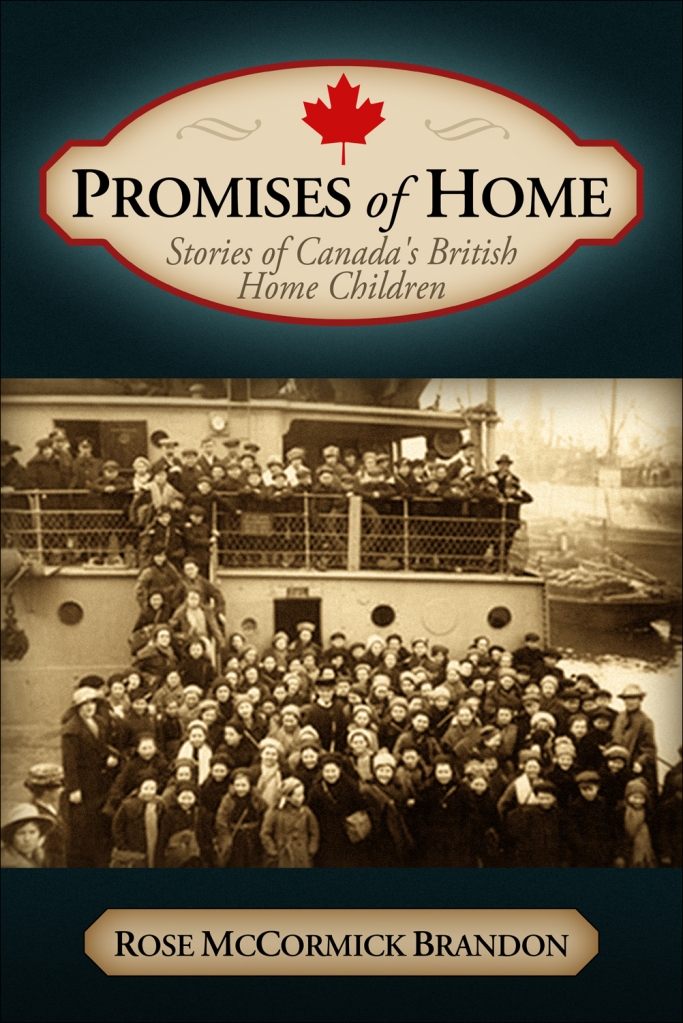

Promises of Home – Stories of Canada’s British Home Children by Rose McCormick Brandon is available here.

Promises of Home – Stories of Canada’s British Home Children by Rose McCormick Brandon is available here.

Kindle edition available at Amazon.

I have really enjoyed this book. I think it’s wonderful how many positive stories there are in it about the Home Children and their experiences. Ivy Sucee, Founder and President, Hazelbrae Barnardo Home Memorial Group

Edward Griffin – by Rose McCormick Brandon

Edward (Ted) Griffin, born in 1900, stepped aboard the SS Corsican, bound for Canada, on August 5, 1912 at age 11. His younger sisters, Grace and Lily, had boarded the same ship on May 14 of the same year.

Edward (Ted) Griffin, born in 1900, stepped aboard the SS Corsican, bound for Canada, on August 5, 1912 at age 11. His younger sisters, Grace and Lily, had boarded the same ship on May 14 of the same year.

Edward, along with his two sisters, was taken to one of The MacPherson Homes in London when he was 5. For many years the family believed they entered an orphanage after the death of their mother. Edward and his sister, Grace, allowed this myth to continue throughout their lives. Through connections with family back in England, the family learned through old letters and other docments that this was not true. They were taken to the MacPherson Home by their step-father, a Mr. Kelly, not long after their father’s death. Their mother didn’t die until 1911, the year before all three immigrated to Canada.

My mother, Mildred (Galbraith) McCormick, niece of Edward, (daughter of Grace), visited England in the 1990s. She and her sister, Evelyn, met with Winnifred, the only child born to Mr. Kelly and Edward’s mother, Esther. Winnifred said then that her father had been a harsh man, even with his own children.

It’s clear Edward held resentment toward his stepfather and blamed him for separating him from his mother. In a letter written in 1928 (Edward’s letters) to his step-sister, Edie Kelly, Edward writes:

“I tried to get around and visit everybody I knew in England when I was there last winter. I didn’t want to see your father as I had no use for him. I guess you know that.”

On arrival in Canada, Edward first went to a foster home (as he called it) in Stratford. It was the MacPherson Receiving Home. At 12, he went to the farm of Mr. Willard Scott at Curries Crossing, near Woodstock, Ontario. He stayed there until age 23, five years after his indentured service ended, indicating that he and the Scott family had a good relationship. He spent the next five years moving around, working on farms in the Toronto area and traveling west. Sometime during this five-year period of roaming, Ted searched for and found Grace. At 20, she was already married with children. It was the first time the siblings had seen one another in 14 years. Lily, Edward’s other sister, passed away in 1921.

At age 28, Edward returned to England, looking for a place that felt like home. During his time in England, he may have visited his Griffin grandmother who lived in Upper Holloway. In his letters to Edie he speaks of trying to visit everyone he knew. This seems to imply that even though he’d been in the home since age five and left England at age 11, he wanted to connect with family. He was also looking for a wife. This is evident in one of his letters. After four months in England, unable to find meaningful employment, or a wife, he returned to the Scott farm in Curries Crossing.

One year later, Mr. Scott sold the farm due to ill health and moved to the city. After that, Edward felt at loose ends. The story is that the Scotts, who didn’t have children, treated Ted like family and left their estate to him. In the letters we have written by Ted, he doesn’t mention much about the Scotts even though he spent many years with them.

Four years after finding Grace, on Manitoulin Island, and after leaving the Scott farm, Ted connected with her again. He spent considerable time with Grace and her husband, James Galbraith, sometimes working for the winter months in a nearby logging camp. Ted had great affection for Grace’s five children, all of whom have happy memories of time spent with their Uncle Ted. He spent Christmases and sometimes spent several weeks with Grace and Jim. He dated a girl for a while, but seemed to find it difficult to make permanent connections with people. His nieces remember him going out with several girls but not taking any relationship seriously. Ted had a difficult time settling down – his letters show a young man who seems lost, searching, unable to stay put for any length of time.

Ted eventually moved permanently to northern Ontario to be near Grace and her family. In 1938, he found work at Inco nickel mines in Sudbury, Ontario. He settled there but remained unmarried until 1953 when he met Jean Buell, a widow with two grown children. First, he was her boarder. Then, the two fell in love and married.

Ted had a reputation for speaking his mind. His niece, Mildred, tells about a humorous incident that happened on one of his visits to their home. The whole family attended a community gathering. A local man, known to be overly-curious, sidled up to Ted and said, “I don’t think I’ve met you before.” Instead of telling the man who he was and where he came from, Ted, in his usual blunt fashion replied: “I’m damned sure you haven’t.” Ted had a confident air and took pride in his appearance.

When Grace and Jim retired from farming, they moved to Espanola, an hour closer to Sudbury and Ted. Two of their daughters lived on the same street. So when Ted visited his sister, his nieces and great nieces and nephews also visited with him. Many Sunday afternoons Ted and Jean came to visit. Jean’s refined manner rubbed off somewhat on Ted. He developed a softer approach to people. Neither Ted nor Grace were resentful of their immigration to Canada, though they both suffered from it in different ways. Grace never talked about her childhood. Ted did. He admitted to being an orphan but not to the fact that his mother had years previous to her death abandoned them. Neither used the term “home child.” In spite of their early hardships, both Ted and Grace were grateful to be in Canada.

Ted was more fortunate than many home children in that he spent his indentured service with one good family and was not moved from one place to another. But, he never lost his yearning to connect with his real family.

When he retired from Inco, in 1965, a photo and article about him appeared in the Sudbury Star. It began

with these words:

front row: Jean, Edward, Grace, Jim (1965)

back row: Grace’s children: Evelyn, Lorma, Ransford, Mildred, Leona

Born in London, England, in 1900, within earshot of the ancient Bow bells, Edward Griffin is proud of his Cockney heritage. Orphaned by the time he was five (Note: he considered himself an orphan, but his mother didn’t die until he was 11), he was raised in an orphanage home (it was a Children’s Home, not an orphanage) until he was 11. In the interview, Edward recalls that he made the sailing on the S. S. Corsican and that the journey took 14 days.

Edward passed away in Sudbury, Ontario in 1978.

Next post: For a look into Edward’s mindset, read his 1928, 29 letters.

Leonard (Bagley) Fraser: In His Own Words

It’s a tragedy when families are forced apart. Leonard Bagley had a mother in England, but circumstances led to the emigration of he and his four siblings to Canada as British Home Children. They were sent to live in five different homes. So often when family bonds are broken it’s forever, but through their own determination the Bagley children managed to reconnect as adults.

The following transcript was made from a taped interview with British Home Child, Leonard (Bagley) Fraser, born January 27, 1899 in Birmingham, Warwickshire, England. Leonard died September 27, 1988 in Michigan, U.S. At the time of the taping, Leonard was the last remaining child of Richard Charles & Leah Bagley. This interview was taped at the Bagley Family Reunion held in Sheffield, New Brunswick, Canada in the summer of 1984.

Grace, Leonard’s wife is interviewing.

— R.M.B.

Leonard: I’ll start at the beginning – 81 years ago last June my brothers, my sister and myself landed in St. John, New Brunswick. We were originally from Birmingham, England. My father died sometime before that, I don’t recall how long. It wasn’t too long. And, of course, my mother, was left with no immediate means of support.

Our (British) government, at that time, was big-hearted enough to put us in a home and eventually ship us over to Canada to get rid of us. So, we went to a home called Middlemore Home. I don’t recall a lot at that time. I was only four years old. I don’t recall how long we were in that home.

I remember when father died. We were setting at a table eating breakfast, I sat in the high chair beside him. He went to lift his knife or his fork up to his mouth, and he fell forward on his face and died. They called it apoplexy at the time. Now a days, it would be called a stroke.

Grace (Leonard’s wife): You came over on a ship. Now what was the name of your ship?

The Siberian. It was 1903 . . . fourteen days coming over . . .

After we landed, I guess most of us on the boat were spoken for. We were sent here more or less as indentured servants, anyway. . . but . . . ah. . . everybody was placed, but me. Course, I was of no use to anybody. I was only four years old. I was the tag end (last one) and sent with a companion.

And now, as I go on I’ll say Mother and Father, to mean my adopted mother and father.

There was a Mrs. Richards who had come as a companion (on the ship), what we would call Social Services now, I suppose. She was a friend of Mother’s. She met Mother on the street one day and she said, “Annie, I have one little boy I’d like for you to see.” So, we were down at the old (Liberty) Hotel and Mother came in and looked me over. Mrs. Richards said, “Would you like to have him?”

Mother said, “Oh, I don’t know. I’d have to ask Wes.”

Note: All five Bagley children arrived on the same ship. Charles 13, Walter 11, Annie Dorothy 9, William 7 and Leonard 4.

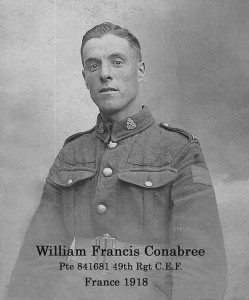

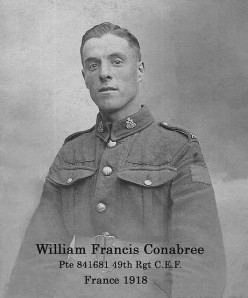

He came down here to a farm owned by a family named Barker. He lived here with them. The way I understand it he had a pretty rough road. He wasn’t abused. But, he was expected to do a man’s work there on the farm. Anyhow, when the war broke out. . . the First World War broke out the 4th of August 1913. He joined the medical corps as a stretcher bearer. He went all through the war . . . was shot up a couple of times. Wound up being gassed and in hospital several times. The gas in the trenches burned his lungs. While recuperating in French hospital he was taught bead weaving as therapy. We have a blue glass seed-bead necklace with a gold seed-bead fleur de lis that Will made while in hospital. By the time Will and the boys came home from France they really should have gotten a full disability pension. Charles told him at the time, “Don’t take off the uniform ‘til you get a pension.”They (Will and wife Florence) fought (for the pension) for years. And when they finally got it it was $16.00 a month. And that’s what they lived on, that and chickens and fishing salmon. Will married Florence Moore from Sheffield. They had Dick, Ken, Jean, Irene, Donna and several years later, Darryl came along. This is the original house they used to live in. (The site of the Family Reunion, then owned by Kenneth Bagley, had been the home of Florence’s parents William & Martha Moore.) Will lived just down the road here.

Wait a minute! By gosh, I do remember one more thing! On our way over somebody sighted a whale! There was a lot of excitement to get the kids up on the deck to see that whale. I remember him coming right along side where I was.

It was 1903….81 years ago. And, that’s the story of my life.

Grace Griffin Galbraith – by Rose McCormick Brandon

On May 14, 1912 Grace Griffin, age 8, boarded the SS Corsican in Liverpool. The ship brought her to Canada along with her 10 year-old sister Lillian. Their older brother, Edward, sailed on the same ship in August of the same year.

Grace is the youngest of 3 children born to Emily Elizabeth Rayner and Edward James Griffin. Her father died at age 28, a few months before Grace’s birth. Grace’s mother then married William Charles Kelly, a nieghbour widower 11 years older, a father of 3.

For many years our family believed that Grace and her siblings ended up at one of The MacPherson Homes when their mother died. That’s what they wanted people to believe. But information shows that they were placed in The Home around 1905 and their mother didn’t die until 1911. William Kelly put his 3 children and Emily’s 3 in the Home. They stayed there for several years. Kelly then took his children back home and left the Griffin children there. When the Kelly children got back home they discovered another child, Winnifred, had been born to Emily and William. Grace didn’t know about this child until Edith Kelly wrote to her in 1928.

Emily Elizabeth died in 1911 at age 33 of tuberculosis. A year after their mother’s death, the three Griffin children became part of the British Child Immigration movement.

Grace first went to a family in Thamesville, then to a home in Perivale, Manitoulin Island. A local minister, Rev. Munro, became aware that Grace was mistreated. He removed her from the Knight home and placed her with the George Gilpin family of Brittainville, also on Manitoulin Island. She stayed with this fine family until age 14 when the Gilpin’s daughter Mable married a William MacDonal. They took Grace to live with them on a farm in Providence Bay. Her association with the Gilpin/MacDonald family was a happy one. Many members of this family remained life-long friends to Grace and some still remain friends with Grace’s children, grandchildren and great grandchildren.

Grace lived with the MacDonalds until she married James Galbraith at age 16 on February 28, 1920. The wedding took place at the United Church in Gore Bay, followed by a wedding supper at the MacDonald home. Attendants were Nelson Galbraith, brother of the groom, and Mae King, friend of Grace. Jim, 29, was a loving husband and good provider.

The two lived on a farm near Providence Bay until their retirement in 1952.They moved to Espanola, a paper town 70 miles from the island. They had five children: Evelyn Legge Pattison (Manitoulin Island), Lorma Middaugh (Evansville, Manitoulin Island – now deceased), Mildred McCormick (Espanola), Leona Sloss (Espanola) and Ransford Galbraith (Mindemoya, Manitoulin Island).

About a year after Grace’s marriage, her sister Lillian died of TB. We know the two had contact by letter until Lillian’s death. In a 1928 letter to relatives back in England, Grace wrote: “It was lonesome for me when Lily died. I missed her sisterly letters.”

Edward (Ted), searched for Grace and found her a few years after her marriage. A bachelor until his fifties, Ted moved near Grace and maintained a close ties with her. As one of Grace’s grandchildren, I remember many of his visits.

My mother, Mildred, is Grace and Jim’s middle child. When they retired from farming, my grandparents built a house two doors from ours. For most of my childhood, I saw my them every day. My grandmother, like many adult home children, didn’t talk about her childhood. If it had been left to her, none of us would know much about her past. But because the community of Providence Bay is small, everyone knew where she’d come from and some of the troubles she’d had. And Uncle Ted was more open about their English past.

Years later, Grace’s son, Ransford Galbraith, was contacted by relatives of her half-sister, Winnie, in England. Grace was well into her eighties by then and had lived alone for a number of years. Ted had passed away a few years earlier.

From the family in England, we discovered Grace had written letters to a step-sister, Edith Kelly, in England. She had never mentioned this woman to her children. Now, every member of our family has copies of these letters written in Grandma’s own hand. In one of the letters, dated July 1928, she wrote, “I can’t ever regret coming to Canada for I have always had a good time. I have had to work hard but I don’t mind that, for I love to work.”

Grace’s letters were written by a young woman pleased with life. She mentions her children and husband with pride. And writes of farm life in words that show she feels blessed and successful. Perhaps the reason Grandma wasn’t as excited as we hoped about re-connecting with English relatives appears in one of her letters. She writes: “I was young when I left there (England) and what little I know of things there I forgot about it . . . I can never recollect of ever seeing my mother and I have no picture of her.” In the same letter she expressed, “a longing to see some of my own folks.”

We received a photo of Grace’s mother, along with other documents, from our reconnected relatives in England.

Grace Griffin Galbraith passed away at age 99. She spent the last years of her life at the nursing home in Gore Bay on Manitoulin Island. At her funeral, the minister (someone who had known her for decades) said that God often makes up for difficult childhood years by putting kind, gentle people into the person’s adult life. This was true for Grandma. Her husband and all five of her children and her 22 children loved and cherished her.

Grace was a loving grandmother, gentle and generous. After a childhood filled with loss – her parents, sister, home, family connections, country – Grace’s longings for family and home came to pass in Canada.

Grace’s eldest daugher, Evelyn, writes: “I feel sad for the unfortunate beginning my mother had but am most thankful for the better life she was offered in Canada.”

Grace died in February, 2003. She would’ve been 100 in November of that year.

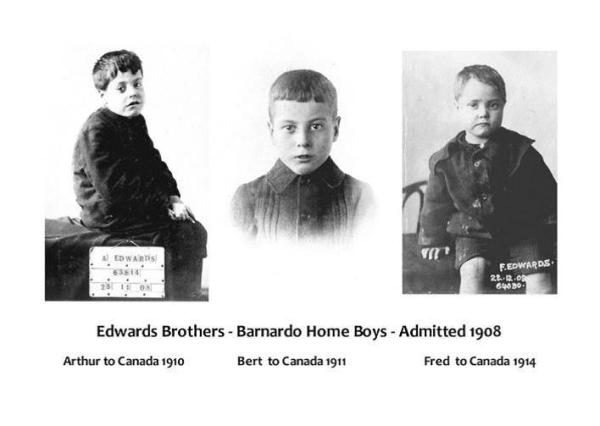

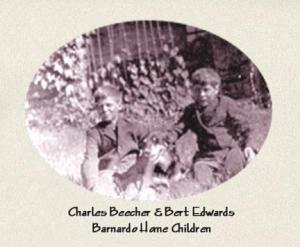

Bert’s first placement in Canada was with a Mrs. Robert Peters in Forestville, Ontario (near Simcoe). It is here that he met Charlie Beecher (BHC 1909) and perhaps even his brother Robert (BHC 1909). The story of Robert Beecher is well known

Bert’s first placement in Canada was with a Mrs. Robert Peters in Forestville, Ontario (near Simcoe). It is here that he met Charlie Beecher (BHC 1909) and perhaps even his brother Robert (BHC 1909). The story of Robert Beecher is well known